Major rivers across Europe are at their lowest levels in years, and climate change will only make things worse for aquatic ecosystems. But allowing nature to take back control can help fix some of the damage.

DW

Major rivers across Europe are at their lowest levels in years, and climate change will only make things worse for aquatic ecosystems. But allowing nature to take back control can help fix some of the damage.

Europe’s intense summer heat waves have brought rivers across the continent to their lowest levels in years.

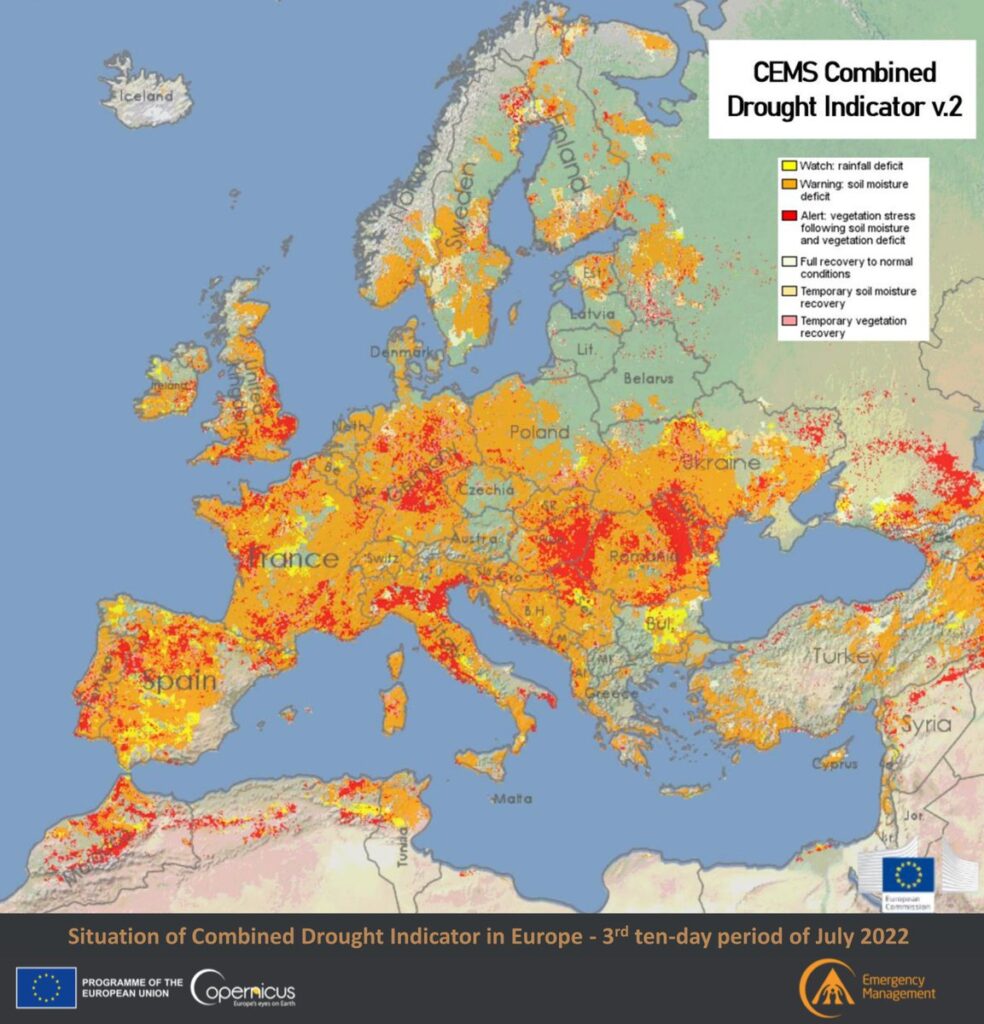

Major waterways like the Rhine, Danube, and Po are warming and at critically low levels, threatening agriculture, commerce, drinking water, and natural ecosystems. The European Drought Observatory has reported that nearly 50% of the continent is under a drought warning, with some analysts calling it in the worst in 500 years.

As we continue to burn fossil fuels that make the planet hotter, heat waves and drought are expected to become more frequent and intense. Countries will have to adapt and deal with the consequences.

What do lower water levels and higher temperatures mean for rivers and lakes?

Lower levels aren’t just bad news for our well-being — they’re also detrimental to the health of rivers and lakes themselves, as well as the wildlife dependent on them.

When water levels fall, living space is restricted and plant and animal populations struggle to coexist, Jose Pablo Murillo, program officer at the Stockholm International Water Institute, told DW. Water quality declines, and ecosystems are disrupted.

And variations in both temperature and levels that are outside normal limits can “quickly increase the risk of drastic changes in the conditions of river and lake ecosystems,” he said.

“This damage is not only limited to the rivers but can extend to adjacent ecosystems upstream and downstream that depend on the services that rivers provide such as drinking water, food supply, irrigation, and nutrients,” Murillo added.

Because warmer waters are hospitable environments for bacteria and other pollutants, drinking water risks contamination. Lower water levels, mean it’s less likely those pollutants will be diluted and washed away.

“When an ecosystem is under high stress for a long period it becomes increasingly difficult for it to recover,” added Murillo.

Harmful algae blooms

Warmer waters also disrupt the delicate balance in aquatic ecosystems.

“Temperature is crucial for aquatic ecosystems as it influences the chemistry of water,” said Murillo. “As the water temperature rises, water holds less dissolved oxygen.” Without that oxygen, it becomes more challenging for the local biota — aquatic plants and animals — to survive.

Some researchers have pointed to low oxygen levels as an aggravating factor in the recent mass fish die-off in the Oder River between Germany and Poland. Historically low water levels since 2018, along with high water temperatures of around 25 degrees Celsius (77 Fahrenheit), mean fish in the river are stressed.

Murillo said lower oxygen levels and increased nutrient pollution can end up stimulating the growth of freshwater algae, a process called eutrophication.

“These issues can reinforce each other,” he said. “For example, higher concentrations of nutrients can result in algal blooms that decrease oxygen levels. This can lead to the death of biota, which increases the nutrient load, and so on.”

That’s the case in Lake Erie, on the border between Canada and the United States, where agricultural nutrient runoff has seen the return of toxic algal blooms in the western basin. Both countries managed to cut algal blooms in the latter half of the 20th century by reducing runoff. But warmer lake waters have seen a recurrence of the algae over the last 20 years, especially in 2011, 2014, and 2015. This has created “dead zones” of depleted oxygen, causing many fish deaths.

Waterways choked with sediment

Parched, slow-moving rivers and shrinking lakes are also much more likely to see an increase in sedimentation. Loose sand, silt, and other soil particles, which would otherwise be swept away, instead settle at the bottom.

This unnatural build-up of sediment destroys the area’s natural habitat by preventing vegetation from growing and damaging food supplies for fish and other aquatic life. In the United States, for example, sediment pollution — from natural erosion and human land use — accounts for around $16 billion (€15.8 billion) in environmental damage every year, according to the country’s Environmental Protection Agency.

Murillo pointed out that this sediment, while a potential problem in one area, might be vital to ecosystems in deltas and coastal wetlands further downstream.

“It can also affect the routes of fish that migrate upstream or the availability of food for wildlife that live by rivers and lakes,” he said.

How can we help rivers and lakes to recover?

Scientists are clear that we must cut climate-altering emissions to address the root causes of drought and extreme heat. But even if we immediately address these challenges, the effects on our waterways will still be felt for decades to come.

There are, however, some things that can be done to give lakes and rivers a helping hand.

One way to keep rivers from overheating is to make sure they’re shaded. Over the past decade, a UK initiative called Keeping Rivers Cool — launched by the Environment Agency government body — has planted more than 300,000 trees along the banks of rivers and streams across the country.

These trees help shade the watercourses and bring temperatures in small rivers down by an average of 2 to 4 degrees Celsius (up to 7 degrees Fahrenheit) — welcome relief for brown trout and salmon populations. One demonstration site along the Ribble River in the northwest recorded shaded areas that were up to 6 degrees cooler on hot days.

The trees also provide a habitat for native plant and animal species, prevent erosion and filter out sediment and pollution before they reach the water.

Reverting rivers to their natural state

Heavily modified rivers are less resilient to global heating and are not able to hold water in droughts and floods. Restoring their natural flow and condition is one solution. That can be achieved by removing unused dams, weirs, and other barriers, allowing the water to flow freely once again.

That’s a major task in Europe. According to 2020 data, the continent is home to at least 1.2 million barriers fragmenting rivers and streams.

Dam Removal Europe, a coalition of environmental groups that include the World Wildlife Fund, the World Fish Migration Foundation, and Rewilding Europe, recorded the removal of at least 239 barriers in 17 European countries in 2021, with Spain, France, and Sweden leading the way.

It’s one of many groups across the continent helping to bring rivers back to a more natural state, along with adjacent wetlands and marshes. Often, native fish and plant species are quick to re-establish themselves once barriers have been removed.

“There are many ways for us to help rivers recover. Overall, we need to reduce the stress we impose on freshwater ecosystems,” said Murillo.

He added that it was essential to consider a “more holistic management of these ecosystems,” one that takes into account how extensively our lakes, rivers, stream,s and oceans are interlinked and dependent on each other.